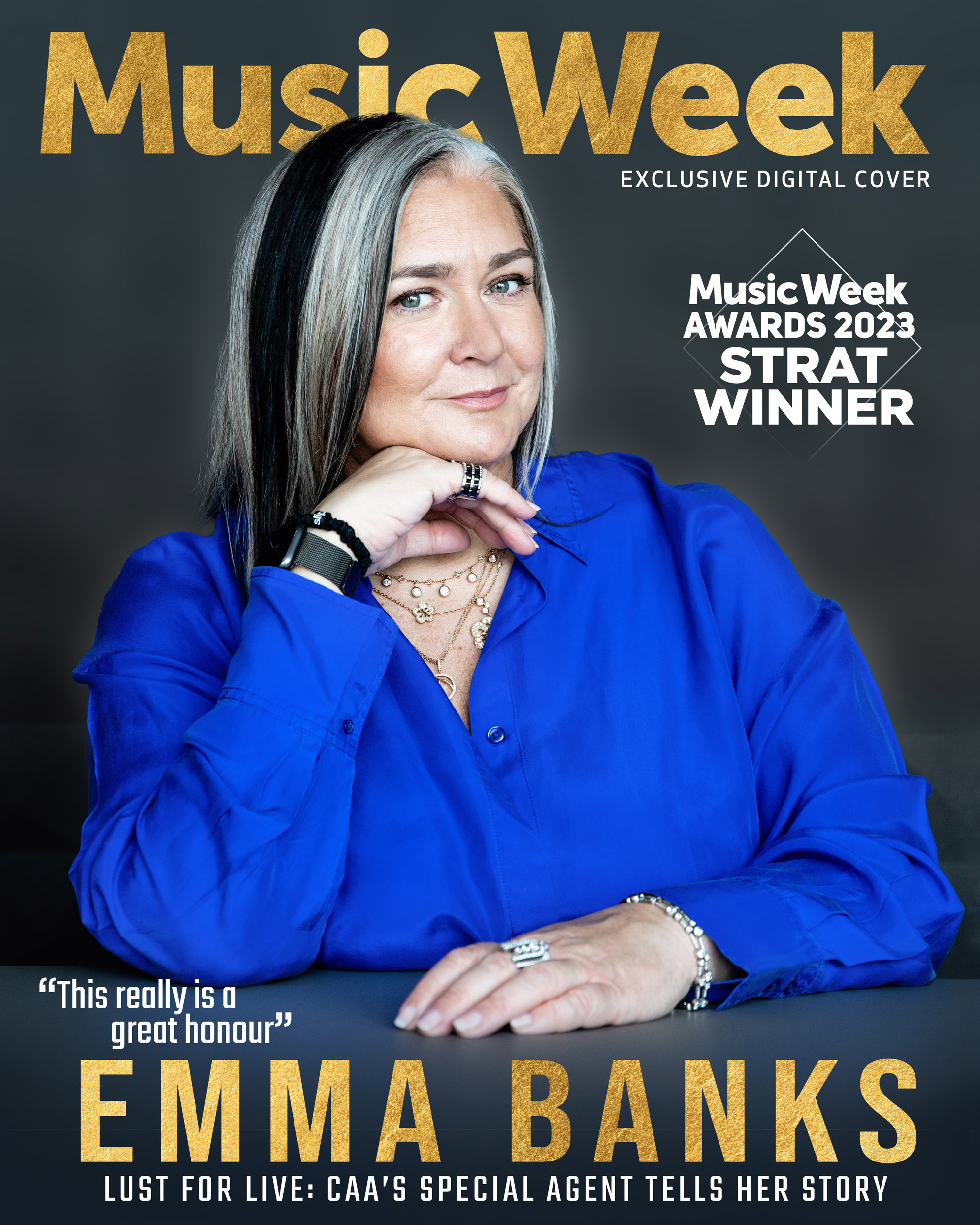

As a trailblazing agent and co-founder of CAA’s UK operation, Emma Banks has played a key role in changing the face of the live industry as we know it. This year, her groundbreaking work was honoured before the industry at the Music Week Awards, as the agent for Katy Perry, Kylie Minogue, Muse and more was crowned winner of The Strat. Here, in celebration of everything she has achieved, Music Week meets Banks for an in-depth account of her story so far and to talk secondary ticketing, grassroots venues and the secrets of dealing with superstars…

WORDS: ANNA FIELDING

PHOTOS: LOUISE HAYWOOD-SCHIEFER

“It’s very grown-up,” says Emma Banks of winning the Strat, the highest honour at the Music Week Awards that was created in 1987 in honour of industry icon Tony Stratton-Smith. Past winners include Barbara Charone, Kanya King, Max Lousada, Darcus Beese, Sarah Stennett and many more.

“It feels like a bit of a freak [thing], being on a list with the previous winners,” continues the CAA agent, who was introduced on stage by her BRIT Award-winning client Becky Hill, while her winners' video featured tributes from Katy Perry, David Joseph, Lucy Dickins, Rob Stringer and many more. “They’re people you’ve heard of before you meet them, and I think our natural state is always to be looking for the grown-up in the room. Then, suddenly, something like this will make you realise you are the grown-up in the room. And that’s terrifying, because I feel the same as when I started, well, perhaps I’ve got more of an idea [of where things are] geographically.”

One particular mistake in this area occurred early in Banks’ career and, speaking from her company’s London office, she smiles as she gives us a potted history.

“It wasn’t a catastrophic trans-continental mess up,” she says. “But I did look at two places, think they were close together and didn’t realise the Alps were in the way.”

Her early phase was spent at the agency Wasted Talent, where she first met her longterm colleague Mike Greek (“He’s my work husband, a brilliant agent and I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for him”). By the time the booking agency became known as Helter Skelter, Emma Banks was at the top of the tree. Then, in 2006, she and Greek co-founded the London outpost of US firm Creative Artists Agency. Her client list now includes global stars and arena fillers like Muse, Kylie Minogue, Red Hot Chili Peppers and Katy Perry.

Winning The Strat stands out for Banks, who won the Music Industry Trusts (MITs) award in 2018 and was honoured by The Cat’s Mother earlier this year.

“Winning this is not just about live music, it represents the whole spectrum of the music industry,” she says. “Everyone who has something to do with contemporary music, be it labels, publishers, streaming services, live, everyone reads Music Week. And Music Week thought I was good enough to be awarded this, so it really is a great honour. There haven’t been as many women who’ve won it as men, and there haven’t been many people from the live sphere. So all of that makes it very special, to be honest.”

Banks feels the live side of the music industry can be overlooked, particularly by outsiders.

“If people, like a researcher on a BBC programme, for example, is looking for someone to talk about stuff, they generally go to record labels,” she says. “Because if you’re on the outside looking in, then it’s record labels who have their logo associated with artists… They’re big and they have big corporate communications teams who are pushing for people to get recognition. A lot of them are public companies now too, so if you’re on the stock market you need to be out there and talking about your results and your projections and what you’re doing. I don't know whether we've all just been a bit more head down, getting on with it.”

Ultimately, Banks says, live is more of a backroom job: “Look, no one goes to see a show because I booked it.”

But while the Alps are still in the same place, the live business has altered during her time in the industry, and winning an award like the Strat gives you cause to take stock.

“Part of your understanding is practical and comes with time,” she says. “You learn which counties are easier to traverse, or where you’ll be held up if it snows. But you also have to consider more rules and regulations now. EU driving laws, UK driving laws, all of the driving laws. People used to do crazy things and stay up all night to get to the next location. And that’s all changed, with tachographs in lorries and so on. And it just means you have to be a little more knowledgeable.”

So much of the live industry is based on getting the timing right and expectations there have also altered over the years.

“We do things very far in advance now,” says Banks. “And you might think that would help with getting organised, but if anything it makes it harder.”

The issue, she says, is that booking tours further ahead gives more time for unforeseen variables to sneak in. It also contrasts with the behaviour of the gig-going public.

“LIVE, the live music industry body that formed through Covid, has just done some research and found that a lot of people are buying tickets a lot later than they used to,” she explains. “I do wonder if we are benefitting from going on sale super early. Are we spending money on advertising that isn’t translating into sales? But, then, if the news of a tour needs to coincide with album pre-orders, that means you’re putting tickets on sale before the album is out, and that could be over a year before the tour takes place.”

When thinking through issues like this, Banks says she often forgets how deep and how specialised her knowledge has become, and that the statements that feel obvious to her might not be obvious to others, even people within the industry.

And while she admits that her vast wealth of knowledge is “one of the good sides of getting older”, Emma Banks is still learning as the industry moves forward. That much is clear over the course of our lengthy conversation. Ostensibly, we’re here to celebrate everything she has achieved so far during a trailblazing career which continues to open doors for others, but that barely scratches the surface. And so we dive into a discussion that takes in everything from protecting the grassroots scene and railing against unfair ticket prices, to the secrets of unearthing new talent, keeping A-list stars on side and rowing a dinghy off the Italian coast with Bono...

Firstly, what does it mean to join the list of executives to have won the award?

“I'm really proud. It’s about being able to say to people that have put time and effort and energy into this brilliant business, ‘Well done, we see you and we see what you stand for.’ But while it's my name on the award, it's about saying, ‘You can't do it without everybody else around you,’ as well. I'm really proud of the fact that I lead an amazing team of people at CAA in London. And they also lead me, it's not that I sit on some throne, dictating, we're all in it together. I've come into my exceedingly messy office to do this interview, but 99% of the time I sit in the open plan office with everybody because that's how I want to work. That's how I love it. We have a laugh, we have a cry, we listen in on each other's conversations, we butt in and we have opinions. I need everyone else's opinion as much as they need mine. I'm really proud that, when I look around, there are plenty of women, there are plenty of men, too, and they're all doing different jobs. We've still got a way to go, it's not 50/50 yet. But as long as we’re aware of [the situation] and you're giving breaks to the people that deserve them, then we can't do very much more.”

Now you have this platform, what’s your message to the rest of the music industry?

“As the older people in the industry, we need to do as much as we can for the younger people. We need to leave this business in good shape for them, because they're starting to take it over. We also need to see what we can do to improve things like the grassroots scene. We need to mentor people, to make it easier for people from backgrounds where they perhaps haven’t had exposure to music because school curriculums seem to cut music before anything else. It’s about asking what we can do to help with things like that. How do we make sure that we have a really diverse population within the industry, be that women, people of colour, everyone. Those are the important things now that we need to look at, as well as making money and being bigger and better than anybody else.”

You said that live is a “backroom” part of the business. Does that mean there’s less ego on your side of the industry?

“Well, we all have egos and I haven’t seen the ego scoreboard! We are entirely dependent on our clients. If you’re a record label or in publishing, then you own IP. You may need to get sign-off on some things, but ultimately you can do what you want with that IP, within reason. But we don’t have that, we do what our clients agree to. If we don’t like the artwork for a poster, we can ask if they’re sure if it’s the best idea, but we don’t have the final say. So I suppose you have to have a bit less ego. We are reliant on an artist wanting to get out of bed in the morning, go somewhere and perform. Whereas if you put their song on a soundtrack, or on a compilation album, or you get someone else to cover it, they don't have to do anything. We deal in one-off experiences. Even on a tour that lasts two years and may have 3-400 shows, and even if each show was choreographed within an inch of its life, there are still slight changes every night. Every occasion is unique. Truly, though, I think agents have to have a level of ego because you have to sell yourself to an artist, their record label and their manager. You have to have enough of a personality to get your message across.”

How do you retain the courage in your convictions when it comes to supporting an act?

“If you don't believe in yourself, you won't be able to sign anybody and you won't be able to sell them to the promoters. And you can't say the same thing over and over again. If I said to every promoter, ‘This is the best artist ever,’ then at some point, they're gonna go, ‘Well, you said that last week, and the one before.’ We all know that this is real life and some acts work better than others, but I think we also have a good idea of those artists that have a big, obvious shot.”

Back in 2018, you told Music Week that agents were “horrible”. Does this mean that you think about yourself this way?

“I think when I said that I was talking about trying to book shows as a student promoter. At that point, agents could be a bit horrible, in terms of not understanding what it was to be a promoter on a budget. It very much felt like, ‘Send us your money and the act will turn up’. And those agents were not really horrible, some of them are still around and some of them are close friends. I think these days there’s more of a culture of service. It used to be that your Rolodex was the most valuable thing because no one else had those numbers. Now, if you know how to use the internet, you can find out what you need to know quite easily. Anyone can be a promoter, so I think all of us have had to do more to justify our positions.”

What other significant changes have taken place in the industry since those days?

“There are so many. You've obviously got way more countries to talk to. When I started, it wasn’t long after the Berlin Wall came down, so Eastern Europe was a new frontier and playing somewhere like Prague was uncharted territory. Brexit has clearly had an influence, Covid has had an influence. Then, specific to the industry, there’s the growth of Live Nation for a start. And global tour deals, which started probably in about 1993, or ’94, but were very, very rare and are now a conversation that everybody's having all the time. You've got way more festivals than ever before, so getting your timings right is harder. Then there’s the amount of sponsorship, not just for tours, but for venues, particularly the opportunities you get with O2 in the UK or Telecom in Germany. Selling tickets on the internet has clearly been a game changer, just because of the amount of tickets we can physically sell compared to 30 years ago.”

Ticketing is perhaps the one area of the live sector that gets the most scrutiny. How do you see this part of the business?

“There have always been secondary ticket sales, but it was on a much, much lower scale, so it didn't really matter. You know, four blokes wearing dodgy macs as you walk up to the venue, it added a little bit of glamour to the occasion. Whereas now, it's totally understandable that people are frustrated if they feel that within 30 seconds of something going on sale, the tickets have disappeared, but they're all on secondary websites for four times more money.”

How can we stop online scalping?

“It needs the big search engines to come on board and stop people buying up AdWords, so that when you search for Beyoncé tickets the first results are legitimate primary sales outlets. But I think we are slowly teaching people that there are places that are safer to buy tickets from than others. Another way to stop it would be to actually fulfil demand. We work in a business where we don’t actually want to fulfil demand because we all want to say our show sold out faster than any other. By selling tickets super-fast, you are allowing scalpers to get in, but if you are more stringent about it, not as many scalpers would be able to buy tickets. But there’s always two sides. I’ve heard it said many times that there’s more tickets on the secondary market selling for under face value than for over. But that’s not as interesting to talk about.”

Where do you stand on ticketing fees, thinking about what’s happened recently in the US with The Cure and Taylor Swift?

“I think what’s really important is transparency, and in the UK we are transparent. We show you the ticket fee and all the add-ons. But there are countries all over the world where the purchaser has no idea how much of the ticket is fees and how much is going to the show. As an agent, I find that very frustrating. We spend a lot of time talking about ticket pricing and thinking about the health of the overall business. Some people just want to extract as much money as humanly possible, but many artists want to feel that their fans are not being gouged. It’s very difficult for me to see how you can justify a percentage of a ticket price as a booking fee. There are some very expensive tickets and they’re often worth it. But if you've got a ticket for £150, it's the same amount of money to administer that ticket sale, as it is to administer a sale of a £15 ticket. That’s certainly my opinion, but I’m sure there's someone in ticketing that's going to tell me I’m completely wrong.”

So are you saying prices aren’t fair?

“I understand there needs to be a minimum service charge, which is the cost of employing people, having customer service and just the cost of all of the technology that goes into ticketing. But it's hard, there are so many prices, so many costs on top. Suddenly there's a heritage charge, a rebuilding charge or a save the roof charge that no one necessarily points out to you when you're planning the day. So a ticket that you thought was going to cost somebody £30, ends up costing them £40. It's a lot of money that the artist is getting. And we know that Ticketmaster and many other ticketing companies make a huge amount of money. But promoters alsof lose a lot of money on a lot of shows. When I started, you did deals that were a guarantee versus maybe 70% of the net revenue. There hasn't been a 70% deal done anywhere that I know for 20 years. And now, you know, at the very top end, you're looking at 90%, 92.5%, 95%, sometimes an even higher portion of the net revenue on a show being paid to the artist, which is great when it works.”

The health of the grassroots scene has also been high on the agenda in recent years. Should the industry do more to support small venues?

“That’s a tricky one isn’t it? When I was growing up, that was one of the relatively few things you could do. You couldn’t make music on your computer because you didn’t have one. But when you look at music that’s doing well now, how much of it has come through the grassroots scene? Or is [that scene] something that exists outside of the chart and the major streaming services? It’s expensive to play shows. You’re doing a gig in a 200-capacity venue, you charge £10 a ticket, you’ve got to pay VAT off that, PRS and rental. Petrol or diesel is the most expensive it’s ever been, even sandwiches from the supermarket. So I think quite a lot about how to help grassroots music venues and those who want to play them. And, also, how can we get people to go to those venues too. Because I’m not sure they’re packed all the time. I am full of admiration for Mark Davyd, the Music Venue Trust and everything they're doing to try and keep it alive, because it's clearly a really important part of the social fabric of the UK. But we also have to persuade people to want to go and enjoy these places. I think people have higher aspirations now than they used to. Again, upgrading facilities is expensive.”

On a related note, what is the best way to break an unknown band?

“The best way of breaking a band is for them to write amazing music. By and large, you have got to just write the best songs ever. And when you think that you've got your album’s worth of songs, write some more, and make them better. You feel like you’ve hit the jackpot when you find an act, hear them for the first time and there are five songs that you feel like you know already. They're interesting, they're clever, they're musical, then go and see them and they've got charisma. Artists can't be apologetic on stage, you've got to own it. And it's not about playing 1,000 shows. To win people over, you might need to play 10 shows to get better in front of an audience. But, actually, you can tour and tour and tour and tour and if you're not good enough, no one will come.”

At the other end of the scale, how do you go about dealing with superstars?

“I mean, they’re superstars and they’re normal human beings at the same time. Often, you've potentially known them since before they were a superstar, so you have a shared history and that can be helpful. You need to listen to them and to understand where their frustrations come from and how it cannot be easy to be constantly on display. Upsetting and hurtful things are said on social media, but you need to relate that to someone who has parents or children, who experiences divorces, relationships and death. They have been prepared to put everything about themselves out there and often the most vulnerable people are the most compelling to watch on stage. You need to be honest with people whilst also delivering what they want. I don’t think there’s a secret, you just try to treat people in the human way you’d like to be treated yourself. It's about being real.”

You must have so many stories from the road. What’s the most interesting thing that’s ever happened to you on tour?

“Early in my career, I was working with Ian Flooks on a U2 tour and I had gone to Naples to cover a show for him. The band were so charming and we ended up going to Positano for lunch in these little boats. I suddenly realised that I’m sitting in a tiny rowing boat with Bono and Paul Oakenfold and Bono is singing Irish sea shanties. And just two years before that, I was standing outside the Reading Hexagon trying to get tickets for The Joshua Tree tour. I had to pinch myself and think, ‘This is really happening, he knows who I am.’”

What keeps the job fun after this long?

“The buzz of a good gig, having an artist that you've worked with and their dream coming true, whatever it is. That's what keeps me going, it really is. I love it. How can you not enjoy that? How can you not get excited about being part of the journey? Agents are the helpers, basically, we're facilitators. We're lucky, because we can say yes. Someone can say, ‘Can we do this?’ And I'll go, ‘Well, I hope so. Let's go and try and do it.’ We're in a lucky position. Ultimately, you do good work, try hard, have good ideas and represent artists in the way they wish to be represented. What we want is to build a team around an artist that remains invested, not just financially. I have an emotional investment in the acts that I work with.”

Going back to your Strat Award win. What do you think having your name on the list of winners will add to the award’s legacy?

“Hopefully people will look at it and say, ‘Yes, she’s a decent person’. Honestly, I'd like to think that most people I've interacted with walk away going, ‘Okay, she's fair, she’s honest.’ To me that is really important. I know I've been incredibly lucky. I mean, as the old saying goes, the harder I work, the luckier I get… But you still have to have some luck, you still have to be occasionally in the right place at the right time. People spend so many hours away from their friends and their families doing this. We are our own community. The live business is its own world. So if you make people feel good about themselves, that's a good thing. I think my legacy can be, you don't have to be an arsehole to be an agent.”