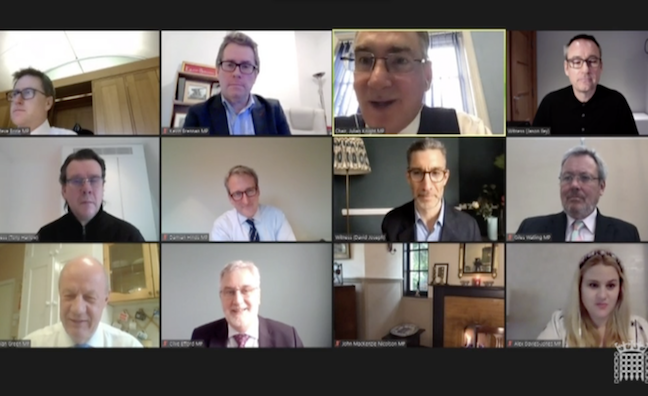

The third session of the DCMS Committee streaming inquiry brought out the country’s top music executives from Universal, Sony, Warner, PRS For Music and PPL. And for the major labels, it was quite a grilling.

MPs freely described the three companies as forming an “oligopoly” and were, at times, forthright in their questioning. And the finale was truly bizarre: David Joseph and committee chair Julian Knight MP trading Harry Potter knowledge (“The performance has been more Hufflepuff today, to be honest with you, Mr Joseph”).

Here’s how the five CEOs handled the virtual session…

Universal Music UK CEO & chairman David Joseph

Like a tough tackle early in the match, Labour MP Clive Efford went in hard with a narrow question about a 2017 global licensing deal between UMG and Spotify that left the door open for lower royalty rates if certain revenue targets were met.

As the market leader, David Joseph was probably always going to be in the firing line. MPs on the committee pressed him further on the lower royalties issue, which the Universal boss was reluctant to answer on commercial confidentiality grounds. Knight was soon comparing this to “dissembling” online giants who had previously appeared before MPs: “So far, you’re beating them to the prize of lack of clarity.” Joseph pledged full disclosure, pointed out that this was an historic deal and there had since been further agreements.

Once the session settled down, Joseph was able to talk about the heightened competition in the streaming era.

“In my 30-plus years of working in the industry, I've never seen a more competitive environment between labels,” he said. On a personal note, he revealed that he hadn’t even spoken to Jason Iley in a couple of years (“we are incredibly competitive companies”), while this virtual encounter with Tony Harlow was the first in a decade.

When MPs questioned him on supporting artists, Joseph felt he had a strong story to tell with 100 new acts signed in 2020. He suggested that plenty of artists who are not household names can earn £100,000-plus a year from streaming.

In my 30-plus years of working in the industry, I've never seen a more competitive environment between labels

David Joseph

All three major label CEOs resisted the suggestion that streaming should be licensed like radio (as performance income rather than a mechanical sale).

“Streaming is 24-7 in every country in the world, you can listen to the greatest record store ever – it's clearly a sale, it's not radio, it's on-demand,” said Joseph.

But of all the execs, Joseph was the most open in suggesting streaming reforms. He didn’t sound much of a fan of the DSPs’ reliance on algorithmic streaming (at one point, he suggested an alternative curated approach for subscribers like BBC Radio 6 Music). And he came close to backing a user-centric payments model that would benefit artists such as Nadine Shah, who’s voiced her concerns about streaming.

“If you just listen to Nadine Shah that month, there would be models the services can do just to pay that artist, rather than be diluted, perhaps, with all the popularity in the label pools,” he said. “There's lots of ways we can approach this. Streaming is not perfect yet. I've got tons of ideas of how to improve streaming for the artists.”

He added: “I’d be very happy to talk when you speak to the streaming services about if there are different ways that artists can be paid and that pie can be split.”

Following concerns raised about whether some artists were fearful of speaking out on streaming royalties, Joseph also underlined his artist-friendly credentials during the pandemic.

“My job is to amplify the voices of our artists,” he said. “I've been speaking to artists two or three times a day, every single day, since March – we're closer than ever.”

Universal has not sold its Spotify shareholding, but Joseph stressed that any proceeds from a stock sale would be shared with artists. And he reminded MPs that the streaming boom follows a period of steep decline.

“We want, obviously, the best deals that we can for our artists and our investment from all of the platforms,” he said. “We've had 15 years of decline, I’ve lived through that decline and what it was like to work in the music industry. We’re starting to grow. All of our artists – and this is essential – are global from day one. It's a growing industry. I think we're great at it: we're less than 1% of the world's population, and 10% of the world's music consumed. I do not think streaming services are perfect. I think there's lots more we can do for the artists.”

Joseph also raised the dominance of YouTube and the issue of the value gap.

After a combative session, the Universal boss actually seemed to be enjoying himself by the end. And he lived up to his reputation as a chief executive who still cares about the songs.

Sony Music CEO & chairman Jason Iley

Jason Iley echoed some of the sentiments of his rival at UMG during his comments to MPs.

“There is more competition in the music industry now than in 30 years of doing this job,” he said. “The independent sector is a brilliant sector and is signing some of the best acts. There's more opportunity for artists to either sign to a major label, sign to an independent label or distribute their own records. There are more avenues today than I've ever seen in my time in doing this job.”

Iley even highlighted three independent acts succeeding without direct major label involvement – Jorja Smith, AJ Tracey and Skepta.

Sony does still have a small holding in Spotify. It previously shared proceeds of divestments with artists and distributed labels.

“None of us in 2006 had any idea that Spotify would be as big as it is today,” said Iley. “I remember sitting in a boardroom and we were discussing the whole concept of streaming. One person, the head of digital in that boardroom, said streaming was the future. And all of us as executives at that time just didn't believe it would happen. We all totally believed in ownership, we never believed that people would not want to open a CD, look at a booklet, read the tracklisting, read the liner notes, we didn't believe it was going to happen. It has, and that is great for the industry, and it is great for artists.”

The Sony boss was also the most open in sharing UK figures, including £20 million spent on A&R and a similar amount on marketing. He mentioned an unnamed new rap artist where Sony had invested the best part of £2 million.

Iley suggested an advance under £200,000 was rare nowadays. He revealed that one-off track deals could be ramped up during negotiations over the course of the day from £50,000 to £300,000 by the time the deal was signed.

“The singles market is a really huge market for one-off singles,” he said.

But Iley was less willing to come out for a new streaming royalty system, such as user-centric payments.

“I look after artists across many different genres, and I have many artists who favour the current model,” he said.

However, he was quick to speak out against the freemium model of services such as Spotify.

“If the ad-funded model went tomorrow, I’d be delighted,” he said.

While there was some tough questioning, Iley also put up a robust defence of the majors and their power in the streaming era.

“The idea that the three major record companies are putting down on the table three exact, similar deals that are take-it-or-leave-it for an artist, feels like something from over 50 years ago, that is not true,” he told MPs. “The modern deals are all different, I do licence deals, I do distribution deals, I do life-of-copyright deals. There are different things that are important to different artists.”

Warner Music UK CEO Tony Harlow

Barely a year in the top job, Tony Harlow was the newest of the three CEOs. But the exec, who has huge international experience, handled himself with aplomb and got the arguments across. He was also strong on detail.

During the early jousting between MPs and the execs, Harlow defended the labels’ control over individual DSP agreements as a way of ensuring against “less good and less effective deals”.

Harlow also stepped in to explain the difference between breakage for physical and digital, amid claims in earlier sessions that streaming artists were still subject to outdated contract clauses (all three CEOs from the majors said that was untrue).

The Warner boss also seemed to get on with Conservative MP Steve Brine, who used his youthful interest in the glam metal band Poison as a way into the royalties debate. “I knew you looked familiar,” said Brine, when Harlow suggested he might have sold him one of the band’s albums while working at Guildford’s branch of Our Price in the ’80s.

But there was a serious point to be made, too, about the new model and the royalties that are paid out.

“We’ve moved from a transaction-based model to a consumption-based model,” said Harlow. “So you [artists] continue to get paid repeated useage of your intellectual property.”

Despite some tough questioning about Warner’s dividend payments, Harlow spoke up for the major’s support of artists in terms of its A&R spend.

“I think we have a very high R&D rate relative to other businesses, it's 30 to 32%,” he said. “And it's heavily focused in the UK where we have artists as diverse as Ed Sheeran. Coldplay, Pink Floyd, Joel Corry…”

“And you also have Led Zeppelin, which I’m delighted about,” added Charles Watling (another MP keen to share his music tastes with the Warner boss). “I do like an album – get it up and you know which track comes next.”

We’re always fighting for the value of music

Tony Harlow

Along with the other CEOs, Harlow also shared some benchmark figures: a million streams brings in between £4,000 and £5,000. Last year, 1,739 Warner Music artists racked up a million streams. And four acts had more than 10 billion streams, resulting in a payout for those artists of “multiple millions” (we can assume Ed Sheeran was among them).

Harlow was also asked about the average 30% share of revenue for platforms such as Spotify – was it too high?

“It’s the result of a market-led negotiation,” he said. “I don't think I can comment on what I think about that level. I think they have substantial and huge costs. They are also run globally and they have many staff. But I really think you have to direct that question towards the DSPs.”

Damian Hinds MP continued on the same theme with a line of questioning that got to the heart of the streaming debate, at a time when classic albums are clogging up the charts. Does that fixed, regular income for labels for repertoire from monthly subscriptions also adequately serve artist development and talent?

“We're always fighting for the value of music,” insisted Harlow. “And that is how I would look at that situation – this is an evolving situation, it is being well governed by a market that’s efficient and nimble. It doesn't need any change, and any disruption could diminish UK competitiveness, at a time when I feel that the UK needs to be the home of recorded music – just as it is by providing one in 10 streams around the world, by being the number two export business. We need to be getting on with making the UK the absolute best place to invest in music.”

PRS For Music CEO Andrea Martin

During the inquiry session, Andrea Martin (who had the best backdrop) raised ongoing concerns about YouTube, safe harbour and the value gap.

“What I want is to make sure that, whenever and wherever music is used online, our members are paid for it,” she said. “It has to be licensed to make sure that there's fair value. When we look at the hosting defence in the EU, or safe harbour in the US, it dates back to 2001 – iPods didn't even exist then, that's almost 20 years. Yes, there has been evolution, but the market is growing really quickly and it has to be modernised.”

With the UK government opting not to sign up to enact the EU Copyright Directive legislation, Martin called for urgent action.

“The UK government has a huge opportunity now to take what the EU has done and improve it, to make sure that the money that is due to our members [is paid] and that more money goes back into the pockets of the creators. I think it's really important that we update that legislation… the hosting defence allows some online platforms to claim that they aren't liable for music.”

Asked about YouTube’s content ID system, Martin said: “I think it’s effective to a certain point, but we have to make sure the content is licensed.”

PPL CEO Peter Leathem

As predicted in Music Week’s preview of the hearing, PPL was quizzed on whether it could take on on-demand audio streaming licensing. Musicians’ Union and PRS For Music member Kevin Brennan asked if the collection society could oversee a new system proposed for “equitable remuneration” (part of the #BrokenRecord campaign).

“From our point of view, we don't particularly have a view about other income streams as to whether or not they should be having certain rights, etc,” said Peter Leathem. “If there were those rights, then obviously we would play a role.”

Warming to his theme, Brennan pressed his alternative model on the PPL boss.

“We’re set up to handle large amounts of repertoire and to make large payments,” said Leathem. “So, yes, if new rights came along we could play a role in administering those.”

But Leathem was more interested in providing a detailed overview of the return to growth fueled by streaming.

“I think when you look at the years of growth that we've had from 2014 to 2020, music is as popular as ever, it's incredibly important to people's identity and to culture,” he said.

Leathem noted the “massive export potential” for UK artists and reminded MPs that the music market actually peaked in 2001.

He also hinted that the unchanged £9.99 price point for streaming subscriptions could be hindering market value growth.

“Spotify, Apple Music, Deezer, Amazon have all been going in a good direction, but their prices have been stuck at £10 since the noughties, so you've then got some limitations there,” he said. “And then also on the value gap, when you look at the 2019 US market - 51% of the streams were from YouTube for 7% of the value.”

When it came to YouTube, the five CEOs were in complete agreement. But, once again, the industry may be left wondering why no one in government or politics is willing to tackle the ever-present ‘value gap’.

Catch up on our reporting of the first two streaming inquiry sessions here and here. And our in-depth report covering all the key issues is here.